Shoulder Anatomy Overview

The shoulder is one of the most complex and flexible joints in your body. It lets you reach, lift, and rotate your arm in many directions. This flexibility comes from a combination of bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and other soft tissues working together.[2-3][7]

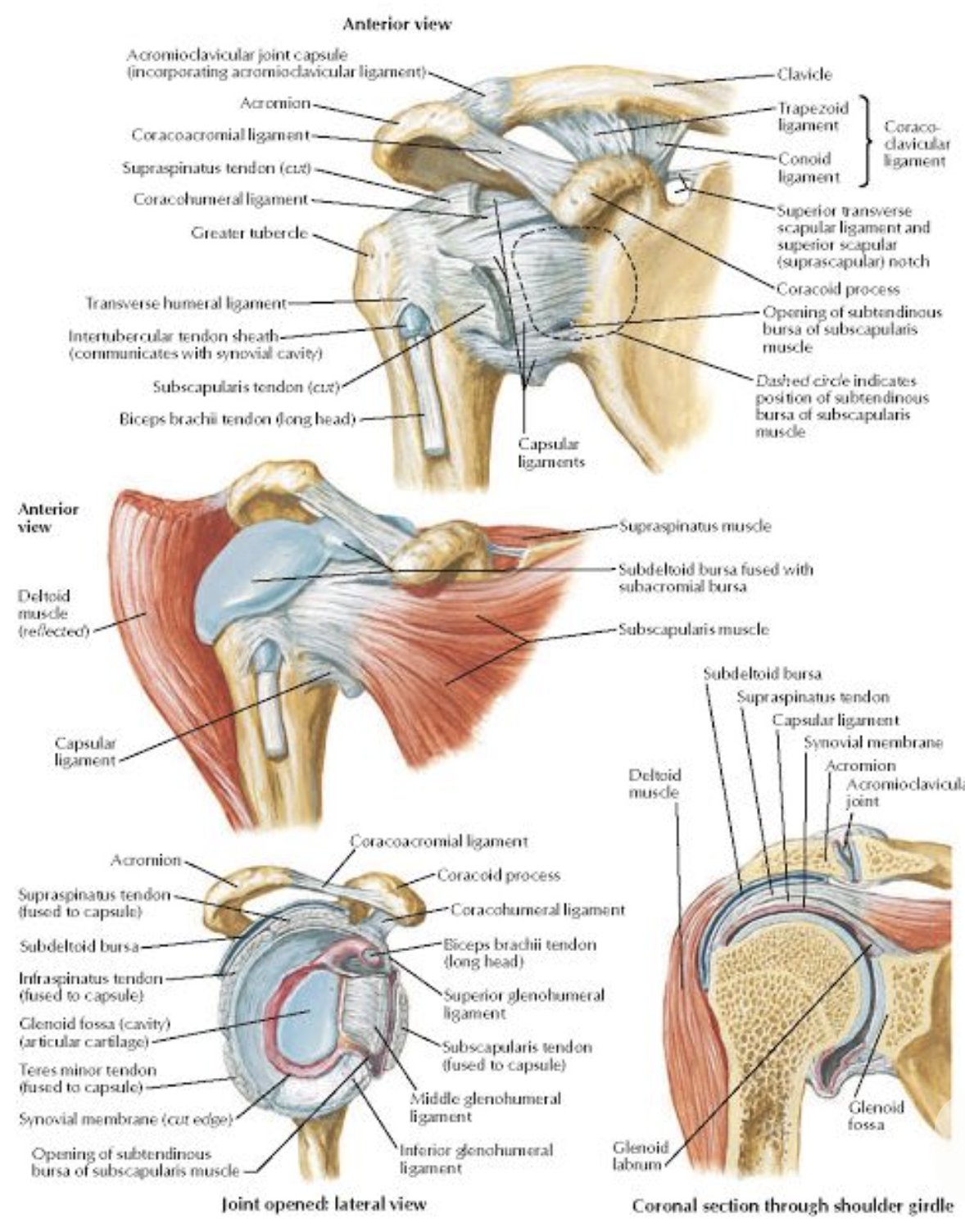

Bones and Joints

Your shoulder is made up of three main bones:

• The humerus (upper arm bone)

• The scapula (shoulder blade), which has two important parts: the acromion (top edge) and the coracoid process (front edge)

• The clavicle (collarbone)

There are four joints in the shoulder area:

• The glenohumeral joint (main shoulder joint): where the round head of the humerus fits into the shallow socket (glenoid fossa) of the scapula

• The acromioclavicular joint: where the acromion of the scapula meets the clavicle

• The sternoclavicular joint: where the clavicle meets the breastbone (sternum)

• The scapulothoracic junction: where the scapula glides over the rib cage[2-3][7]

Muscles and Tendons

Seventeen muscles help move and stabilize your shoulder. The most important group is the rotator cuff, made up of four muscles:

• Supraspinatus: starts lifting your arm away from your body (abduction)

• Infraspinatus: helps rotate your arm outward (external rotation)

• Teres minor: also helps with outward rotation and some adduction (moving arm toward body)

• Subscapularis: helps rotate your arm inward (internal rotation) and adduction[2][5][7-8]

These muscles attach to the bones by strong cords called tendons. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons keep the shoulder stable and help with movement, especially during activities like throwing or reaching overhead.[2][5][8]

Other important muscles include:

• Deltoid: covers the shoulder and lifts the arm

• Pectoralis major: chest muscle that helps move the arm forward and inward

• Latissimus dorsi: back muscle that helps pull the arm down and back[5][8]

Soft Tissues and Ligaments

• The glenoid labrum is a ring of cartilage that deepens the shoulder socket and helps keep the humerus in place, acting like a bumper.[3-4][6][9]

• The joint capsule is a thin, flexible tissue that surrounds the joint and holds fluid for smooth movement.[3-4][6][9]

• Ligaments are tough bands that connect bones and help keep the joint stable. The main ones are the glenohumeral ligaments (superior, middle, and inferior), which strengthen the capsule and limit excessive movement.[3-4][6][9]

• The bursa is a small fluid-filled sac that reduces friction between muscles and bones, especially above the rotator cuff.[2]

Static vs. Dynamic Stabilizers

Shoulder stability comes from two types of support:

• Static stabilizers are structures that do not move. These include the bones, labrum, joint capsule, and ligaments. They help keep the shoulder in place, especially when the arm is at rest or at the limits of its movement.[1][3-4][6][9]

• Dynamic stabilizers are the muscles and tendons, especially the rotator cuff. These actively adjust and balance the shoulder during movement, keeping the joint centered and preventing it from slipping out of place.[1-2][5-8][10]

How It All Works Together

The shoulder’s wide range of motion is possible because the socket is shallow and the joint is supported by both static and dynamic stabilizers. The rotator cuff muscles are especially important for keeping the humeral head centered in the socket during movement, while the ligaments and labrum prevent the joint from moving too far.[1-10]

Injuries to any of these parts—like a torn rotator cuff, damaged labrum, or stretched ligaments—can lead to pain, weakness, or instability. Keeping shoulder muscles strong and flexible helps protect the joint and prevent problems.[7-8][10]

If you have shoulder pain or trouble moving your arm, understanding these structures can help you talk with your healthcare provider about the best ways to treat and protect your shoulder.

References

Hermans J, Luime JJ, Meuffels DE, et al. JAMA. 2013;310(8):837-47. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.276187.

Does This Patient Have an Instability of the Shoulder or a Labrum Lesion?.

Luime JJ, Verhagen AP, Miedema HS, et al. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1989-99. doi:10.1001/jama.292.16.1989.

Functional Anatomy of the Shoulder.

Terry GC, Chopp TM. Journal of Athletic Training. 2000;35(3):248-55.

Lines of Action and Stabilizing Potential of the Shoulder Musculature.

Ackland DC, Pandy MG. Journal of Anatomy. 2009;215(2):184-97. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01090.x.

Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Shoulder in Throwing, Swimming, Gymnastics, and Tennis.

Perry J. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 1983;2(2):247-70.

Glenohumeral Stability. Biomechanical Properties of Passive and Active Stabilizers.

Bigliani LU, Kelkar R, Flatow EL, Pollock RG, Mow VC. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1996;(330):13-30.

Current Concepts: The Stabilizing Structures of the Glenohumeral Joint.

Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1997;25(6):364-79. doi:10.2519/jospt.1997.25.6.364.

Arthroscopic Alphabet Soup: Recognition of Normal, Normal Variants, and Pathology.

Yin B, Vella J, Levine WN. The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2010;41(3):297-308. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2010.02.003.

Lugo R, Kung P, Ma CB. European Journal of Radiology. 2008;68(1):16-24. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.02.051.

Stability and Instability of the Glenohumeral Joint: The Role of Shoulder Muscles.

Labriola JE, Lee TQ, Debski RE, McMahon PJ. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2005 Jan-Feb;14(1 Suppl S):32S-38S. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.014.

Courtesy of Netter Atlas of Human Anatomy